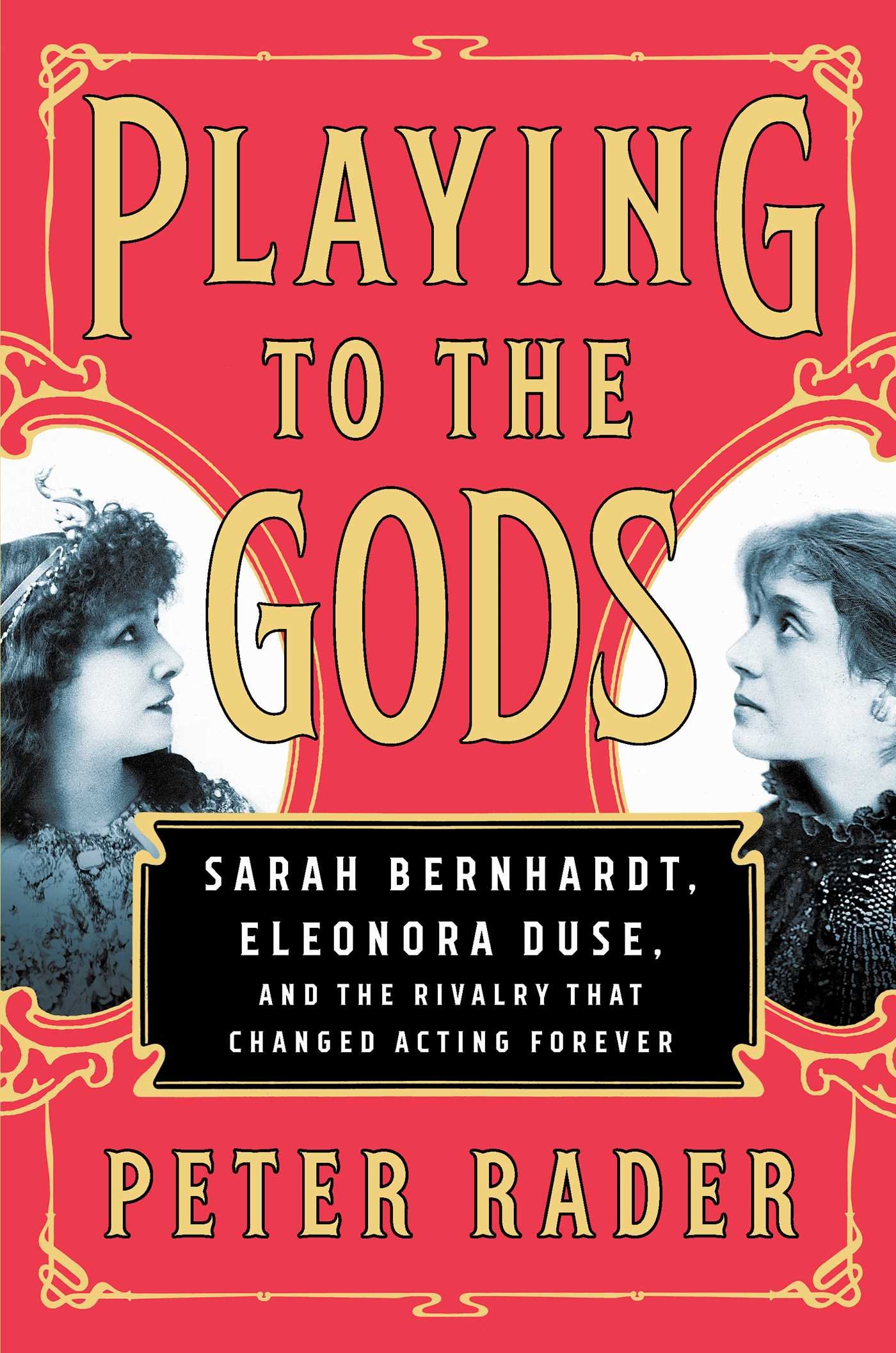

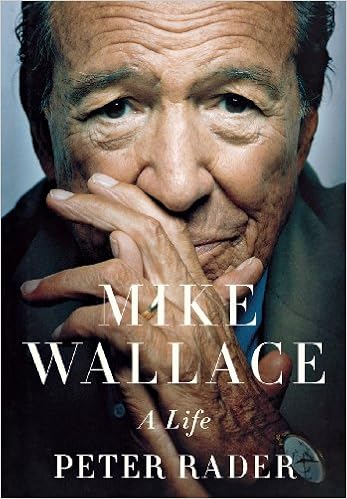

Peter Rader AB '82-'83 began his career as a screenwriter, penning blockbuster Waterworld on spec and developing projects for the likes of Steven Spielberg and Dino De Laurentiis. Since then, Rader has directed episodes of hit series Dog Whisperer with Cesar Milan and produced several documentaries under the banner of CounterPoint Films, the TV/film production company he runs with his wife, Paola di Florio. Rader is also the author of two non-fiction books, Mike Wallace: A Life (St. Martin's Press) and—published earlier this year—Playing to the Gods (Simon & Schuster), an account of the longstanding rivalry between legendary actresses Sarah Bernhardt and Eleonora Duse.

Peter Rader AB '82-'83 began his career as a screenwriter, penning blockbuster Waterworld on spec and developing projects for the likes of Steven Spielberg and Dino De Laurentiis. Since then, Rader has directed episodes of hit series Dog Whisperer with Cesar Milan and produced several documentaries under the banner of CounterPoint Films, the TV/film production company he runs with his wife, Paola di Florio. Rader is also the author of two non-fiction books, Mike Wallace: A Life (St. Martin's Press) and—published earlier this year—Playing to the Gods (Simon & Schuster), an account of the longstanding rivalry between legendary actresses Sarah Bernhardt and Eleonora Duse.

Q. It’s been over 10 years since Harvardwood last chatted with you, and so much has happened since then! You’ve worn many different creative hats throughout your career: you’ve written movies, directed for TV, produced documentaries, not to mention your numerous credits as an editor and cinematographer… and you’re also a nonfiction author of two books! Aside from the obvious common thread—storytelling—can you talk about the skills, passions, or knowledge one needs to accomplish all of the above?

A. It really does just come down to the storytelling aspect. There’s a quote by a French Jesuit priest, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin: “We aren’t human beings having spiritual experiences. We are spiritual beings having human experiences.” This quote has haunted me the past few years.

All the things we do as creators of arts are a little hint of what it means to be a spirit having a human experience. Our bodies do not have owners’ manuals. The human condition is quite daunting and confusing. Narrative storytelling is a way for us to come to an understanding of a shared humanity—you have your experiences, and your experiences can actually inform how I navigate through this life.

That is really my passion: playing around with the idea that we need to create, share, and disseminate narratives that help us navigate this human condition.

Q. Congratulations on the recent publication of your latest nonfiction book, Playing to the Gods: Sarah Bernhardt, Eleonora Duse, and the Rivalry that Changed Acting Forever. What attracted you to the story of these two women?

A. In theater, we get to take this anthropological stance; we are in the audience observing other humans in their platform, playing out various human dramas—we’re almost like zoologists.

A. In theater, we get to take this anthropological stance; we are in the audience observing other humans in their platform, playing out various human dramas—we’re almost like zoologists.

In fact, one of the subjects of the book, Eleanora Duse, created the illusion of the fourth wall. She was one of the first actors to ignore the audience; she never made eye contact with her audience until curtain. It gave the audience that thrilling experience of being voyeuristic observers of a woman who wants to leave her husband or who is having trouble with her siblings, whatever play she was in.

Sarah and Eleonora’s story, and the story of this project, is one of perseverance and persistence. I began exploring this narrative over 25 years ago. It began as a script that actually got quite a bit of traction—various actors, producers, and directors were attached in script form.

This is a story about rivalry as well. I got a sock in the stomach when I found out there was a rival project by someone else. And it wasn’t just any “someone else.” It was Dan Jinks and Bruce Cohen, producers of American Beauty, with Spielberg to direct. At that point, my project died, and it was heartbreaking. Years went by. Nothing was happening with their project.

So I said, “You know what? I’m going to write this into a book, and maybe it’ll make its way back into movie form.”

Q. And will it?

A. What’s incredibly ironic is that Spielberg eventually walked away from this project and it was assigned to Grey Gardens'Michael Sucsy. We sent Michael the book earlier this year, and he optioned it. Now Michael and I are collaborating on the story. He’s an auteur, a writer-director-producer, and I’m thrilled to hand it off to him. Collaborating with him has been so heartening; he’s one of those collaborators who keep elevating things.

Q. Can you talk a little bit about the different challenges between creating an original work versus adapting existing material, whether it’s someone else’s or your own?

A. In the case of Playing to the Gods—especially a dueling biography of two incredibly rich lives with many phases, ups and downs, lateral moves, and all sorts of complications—it’s about choosing which part of the story to tell. The devil is in those details. You cannot do cradle to the grave, so where are you going to start? What’s the juiciest part of this narrative?

Q. What drew you from years of filmmaking to writing your first nonfiction book, Mike Wallace? Was there a reason you decided to write a book instead of, say, doing a documentary?

A. That book was birthed during the writers’ strike. I was sitting around, twiddling my thumbs, thinking about what to do. My sister had worked for Mike Wallace for a number of years, so I had an insider’s scoop on some aspects of the story.

A. That book was birthed during the writers’ strike. I was sitting around, twiddling my thumbs, thinking about what to do. My sister had worked for Mike Wallace for a number of years, so I had an insider’s scoop on some aspects of the story.

It definitely had the mythic grandeur that I love in stories, the Shakespearean, larger-than-life hero with a tragic flaw. During the writers’ strike, I thought, “I’ve always wanted to write a book. Why not use this opportunity to explore that format?” I wrote a proposal, which was snapped up by St. Martin’s Press.

Q. For you, how is the writing process for a book distinct from writing for film or TV?

A. The beautiful thing about writing a book is that it’s just you and the words. From a writer’s point of view, there’s something emancipating about not having a Hollywood committee of executives giving you notes at every stage. I was so liberated by being able to construct a narrative on my end. Of course, there’s a round or two of edits with your editor, but that’s a one-on-one process.

Q. Speaking of, last time Harvardwood chatted with you, you mentioned the development hell that your very successful spec feature WATERWORLD went through. Looking back with even more distance today, how did that experience as a young writer shape your career later on?

A. I now understand much more clearly my purpose and what it is that I’m meant to be doing on this planet. I’m more comfortable in determining which projects I want to attach myself to and why they’re important and why they’re worth fighting for.

Before, it was more like the opportunities are coming and knocking, and I’m just grabbing them as they’re flying by me. It was a little haphazard. And after Waterworld, I got pigeonholed into writing sci-fi. Each time, it was reinventing the wheel from scratch: the rules, textures, and geography of a new world. [Sci-fi movies] are incredibly expensive, so people are nervous and there are lots of notes. Development hell!

Q. And how did you escape the trappings of development hell?

A. When I met my wife 23 years ago, Paolo di Florio, she exposed me to the beauties of the indie filmmaking scene. She’s had a couple of movies at Sundance [and showed me] this idea of making movies on a more manageable scale where there’s more independence and less interference. That took me away from Hollywood studio writing for a while, and the nonfiction books I wrote were part of that move. I took a detour in a career path that I found fulfilling.

Q. You and Paola run a production company, Counterpoint Films, together. How is it working so closely with a partner professionally and personally? Do you have parameters on discussing work at home, vice versa?

Q. You and Paola run a production company, Counterpoint Films, together. How is it working so closely with a partner professionally and personally? Do you have parameters on discussing work at home, vice versa?

A. When it’s good, it’s fantastic. And when it’s bad, it’s pretty bad.

We’ve worked together since very early on in our relationship. We were dating and dived into making a film together, a documentary called Speaking in Strings. She was writing and directing, and I jumped in as a cameraman. I had some skills, I’d worked below the line a little bit, and I said, “Let’s put this on a credit card and start filming this thing.”

The documentary tracked our relationship from just dating to, later on, our engagement, our marriage, and when we had our first kid. In the course of those years, this little film that could, which we started on home prosumer equipment, a Hi8 camcorder, became a Grand Jury Nominee at the 1999 Sundance Film Festival and received an Academy Award nomination for Best Feature Documentary Film. It was a really joyful and fun experience.

More recently, we did another documentary together, Awake: The Life of Yogananda (watch the trailer). That was great, but it was also quite challenging because we had two young kids and we had to bring them to India to shoot for six weeks.

So the challenges of working together with your spouse are just the logistics of having to wear the parenting hat and the spouse hat and the work hat. But the advantages are the communication shorthand, being able to reach other’s minds, and knowing creatively where we are and what things are worth pursuing.

Q. Are there any upcoming projects you can tell us about?

A. We’re very close to announcing another big project in India that’s going to be a three-day music and peace festival!